Including dentistry in Medicare

What do we mean when we talk about expanding Medicare to include more dental services? Does that mean free care for everyone?

There has been a lot of talk about expanding Medicare to include more dental services, but there is still a lot of confusion about what there really means. There are also plenty of misconceptions – with many people assuming that it would automatically mean free dental care for everyone.

Firstly, why are we even having this conversation?

A few years ago the Senate Select Committee into the Provision of and Access to Dental Services handed down their final report, which made a number of recommendations. The Senate heard from 84 witnesses including a range of experts across oral and general health including professional associations, public dental services, academics and front line clinicians, as well as receiving a staggering 17 592 public responses to a survey.

The stories that they heard were heart-breaking:

‘The pain in my mouth affects my general well-being and the lack of regular, basic dental care takes away dignity and self-respect as well as inability to enjoy food properly.’

They heard about the many barriers that people experienced trying to access dental care, including high costs, trauma and fear, long waiting times and inaccessible services, with gaps including a lack of special needs dentists, limited mobile services, very few Aboriginal dentists and sparse services in regional areas.

The net result is that too many Australians suffer poor oral health with all of the associated impacts such as pain and suffering, shame and low self-esteem, poor nutrition and poor general health.

Poor oral health continues to be one of the strongest indicators of disadvantage in Australia.

The Senate Committee final report made a number of recommendations, one of which was to work with the states and territories to achieve universal access to dental and oral health care, which expands coverage under Medicare or a similar scheme for essential oral health care, over time, in stages.

What is universal health coverage?

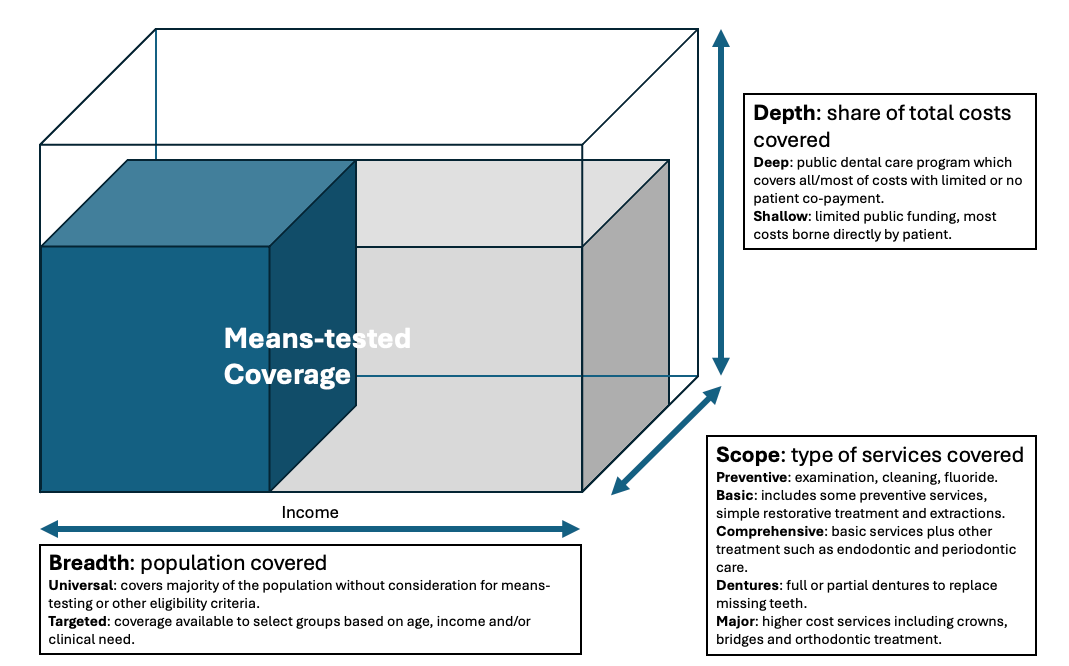

The concept of universal health coverage is that all people should be able to access the quality of health care that they need without facing financial hardship. It is the basis that underpins Medicare for health services in Australia. There are essentially three dimensions to universal health coverage:

Breadth - the extent of the population covered

Depth - the share of costs covered by governments

Scope - the range of treatments or services covered

Universal coverage is best depicted with the universal coverage cube. In an ideal world, we want a healthcare system that provides the broadest possible population coverage, with a wide scope of treatment provided with deep coverage where most of the cost is covered by public funding. Any gaps that exist, in terms of population groups, dental services or costs not covered must be borne by individuals, through a combination of out-of-pocket payments and insurance.

Now look at the Child Dental Benefits Schedule (CDBS) as an example. The breadth is somewhat narrow – firstly in that it only applies to children (about 25% of the population), but then it’s targeted based on income to only around 50% of children. Next is the scope – most, but not all items in the dental item schedule are covered by the CBDS. And finally the depth of coverage – the CDBS rebates do not completely cover the cost of providing the service, and whilst the majority of dental practitioners do in fact bulk bill, many charge their patients a co-payment or gap.

What did the Senate Committee recommend?

The Senate Committee set forward a range of options to improve access to dental care by moving towards universal coverage.

Option 1: Universal coverage of dental services

This option proposed rebates based on the CDBS schedule of fees for all Medicare care card holders. This would cover the full breadth of the population, with a wide (but not complete) scope of services and with a depth of coverage that would cover most, but not all of the costs of provided treatment.

For this (and all of the other options proposed) there was further consideration to either having a capped scheme similar to the Child Dental Benefits Schedule, which would mean for example a limit of up to $1052 over a 2 calendar year period to contain costs, or an uncapped scheme, replicating what happens with Medicare where patients can access unlimited care based only on their clinical needs.

The Parliamentary Budget Office costed universal coverage at around $6 billion (capped) to $8.3 billion (uncapped) per year.

Option 2: Means-tested coverage

In this scenario, the breadth of coverage would be restricted to health care card holders, pension card holders and those on government income support—consistent with current means test requirements for the CDBS. For adults, this would represent around 30-40% of the population and would ensure that the scheme would be available to those who experience the greatest challenges in accessing dental care, and who also tend to experience the greatest disease burden. The Parliamentary Budget Office costed universal coverage at around $2 billion (capped) to $2.8 billion (uncapped) per year.

Option 3: Seniors dental care

This recommendation mirrors that made by the Aged Care Royal Commission, and would be even more narrowly targeted to holders of Commonwealth seniors health cards, pensioner concession cards and health care cards who are 65 years or older. Nearly 20% of the Australian population is aged 65+ years, and a high proportion of those would be eligible to access this scheme. This would effectively replicate the Child Dental Benefits Schedule for older adults, coverage a proportion of the population with broad scope and depth of coverage. The Parliamentary Budget Office costed universal coverage at around $1.1 billion (capped) to $1.4 billion (uncapped) per year.

The major limitation here is that it leaves a large gap in the population breadth of coverage from 18 to 65 years. There is evidence that many younger people drop out of regular care around the age of 18-25 years, and this model poses a risk for many younger Australians who would continue to miss out on care.

Option 4: Funding preventative care only

Under this option, the breadth would be the whole population of Medicare card holders, with a scope of all items listed as Diagnostic or Preventive in the Child Dental Benefits Schedule. The key limitation here would be the very narrow scope of coverage. The Parliamentary Budget Office costed universal coverage at around $1.9 billion (capped) to $2.7 billion (uncapped) per year.

There are obvious pros and cons to the different options as the levers are adjusted to increase or decrease the scope, breadth and depth of coverage, and it is important to note that these are broad proposals for ongoing discussion, not hard policy positions that are set in stone.

Essential Dental Care

If we decide to further reform our public dental funding system, we need to think about those three dimensions of the universal coverage cube. Should we provide subsidised dental care to the whole population, or target to certain population groups? Where should we set the subsidy or rebate level to balance the overall budgetary impact with the ability for people to access affordable care?

And importantly, where do we draw the line on the scope of services covered - in essence, what constitutes essential oral health care. This has been defined in the literature as treatment for the most prevalent oral health problems through safe, quality, and cost-effective interventions at both the individual and community level to promote and protect oral health, as well as prevent and treat common oral diseases, including appropriate rehabilitative services. But would would this look like in practice?

This is a critically important debate for the dental profession, as we grapple with a growing proportion of the population who struggle to access dental care at a time when the disease burden appears to be increasing. We have an opportunity to learn from the Child Dental Benefits Schedule which has operated successfully for 10 years, and build that out to other population groups. The federal election is shaping up as a battleground for oral health, and as a profession we need to be at the forefront, fighting to ensure that our patients, and that the whole community, get a good deal.

Give Medicare Teeth Campaign

The Give Medicare Teeth campaign was launched on World Oral Health Day on 20 March. To date it has had good reach across a range of social media platforms, great engagement and support from the public and thousands of visits to the campaign website. Nearly 100 people have let us know that they have emailed their candidates in the upcoming election, and a number of those candidates have let us know that they are committed to supporting action to improve access to dental care if they are elected to the next parliament.

Monique Ryan (Kooyong) supports including dental care in Medicare.

Ben Ryan (Flinders) wants to expand Medicare to include basic dental care starting with seniors.

Helen Huang (Melbourne) says that Medicare should also cover essential dental and mental health check-ups.

Caz Heise (Cowper) supports the recommendations of the 2023 Senate Committee and will advocate for their implementation, starting with expanding Medicare to cover essential oral healthcare and properly funding the public system to end long wait times.

If you believe that there is a need to improve access to dental care in Australia, regardless of which particular model that you support, I encourage you to visit the Give Medicare Teeth website, find your electorate and email your candidates and ask them to commit to action. You can download social media tiles to share the message across your network.